Long Beach Island is what is known as a barrier beach. The island was once a place where nature dominated but this has changed with all the human developement that has taken place. Natural forces can still wreak havoc here with both winter storms taking away beach sand and voilent storms leading to the ocean breaching the island itself.

There are numerous natural habitats that occur on LBI. These are now marginal portions of the island and, excpet for the beach itself, many summer visitors never know about these areas or ever see them. These pages are designed to be a place for the curious to learn more about nature on Long Beach Island, along the Jersey shore, and within some of the natural environments that make up and surround the barrier island.

Shells of the New Jersey Coast

Long Beach Island Bird Checklist

Barrier Islands

About 300 major barrier islands are strung out along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States. Each has a similar patterning of habitats that go from, in moving from the ocean to the bay, from offshore sandbars, beach, grassy dunes, maritime forest, tidal salt marsh to open. Undeveloped barrier islands are dynamic systems that change dramatically through time. Sandy beaches erode when pounded by strong storm driven high tides. This in turn releases sand from the dunes to the each, with the dunes gradually rebuilding themselves between each erosion event. More dramatically, the islands themselves can shift as their sands are buffeted about from year to year. Erosion on one end of a barrier island and/or build up on the opposite side can occur. These islands can even roll slowly back on themselves as sand is carried away from the beach by the wind. Dunes enchroach on the maritime forest, the forest pushes back into the marsh, and the marsh pushes back into the bay. This can widen the island for a time, at least until the beach is eroded and naturally replenished. The beach can regenerate to the point where it may be the same width as before but the shoreline will shift west of were it once was. When houses are built at the edge of the beach or where the dunes once stood, natural processes can instead work to erode but not have dune sand to help replenish sand that was lost.

Migratory Shore Birds

Long Journey

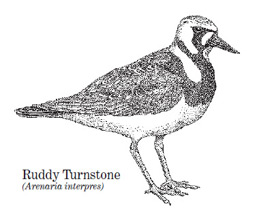

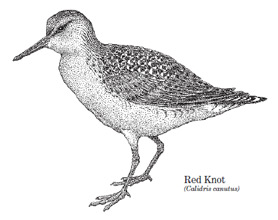

Shorebirds occur throughout the world and are a familiar sight to visitors and residents of our coastal shores and waterways. These remarkable birds have some of the longest migrations known, traveling from their wintering ground at the tip of South America to their Arctic breeding grounds and back again each year. Their migration also includes some of the longest non-stop flights in the bird world, commonly exceeding 1,000 miles. Stopovers like Delaware Bay play an important role by providing food resources for these birds at critical times during migration. Over half of the Western Atlantic Flyway’s population of red knot, ruddy turnstone and semipalmated sandpiper may rely upon Delaware Bay in the spring to replenish their energy reserves before heading to the Arctic nesting grounds.

Compressed Time Schedules

The northbound migration of red knots usually begins in mid-February as they leave their wintering grounds at the tip of South America and move up the coast of Argentina. By mid-April they have reached southern Brazil, their last South American stop for food. By the middle of May, large numbers of red knots arrive at Delaware Bay. By the end of May or the first few days of June they have departed on the final leg of their journey to their Arctic nesting grounds.

To breed successfully in the Arctic, the birds arrive just as the snow is melting in early June. They have just enough time to establish nesting sites, perform courtship displays, incubate eggs and replenish their energy reserves by feasting on the abundant insect life before setting off on their southbound migration in mid-July. Because the Arctic season is so short, there is no room for delay.

The birds arrive in the Arctic before insects emerge. This means that the birds must leave Delaware Bay with enough energy reserves to make the trip to the Arctic and survive without food until well after they have laid their eggs. If they have not accumulated enough fat reserves at Delaware Bay, they may not be able to breed.

Balancing the Need for Flight With the Need for Fuel

To accomplish such feats of migration endurance, shorebirds must have large amounts of fat for fuel, but their wing size and muscle strength limit how much weight they can lift. Therefore, they must carefully balance their need for fuel with their ability to fly. Some shorebirds can dramatically change the size of their internal organs in preparation for feeding or flight.

When red knots arrive at Delaware Bay in the spring, they have lost all their fat reserves and some muscle mass. It takes several days before they begin to gain weight. During this time, their stomach, intestines, kidneys and liver are enlarging as they rebuild their digestive system. The birds then put on weight at an astounding rate, gaining more than 4 percent of their body weight each day, which is comparable to a 150-pound person gaining more than 6 pounds a day. After they have gained sufficient weight, the birds spend several days resting without eating. During this time, they reduce the size of their internal organs since their primary needs are to fuel the flight and the first part of their breeding season. Every ounce counts as they balance the competing needs for fuel and flight to meet the demands of their compressed breeding season.

The Horseshoe Crab Connection

The world’s largest spawning population of horseshoe crabs occurs in Delaware Bay. A single crab may lay 100,000 eggs or more during a season. While the crab buries these eggs deeper than shorebirds can reach, waves and other horseshoe crabs expose large numbers of eggs. These surface eggs will not survive, but they provide food for many animals.

The shorebirds are especially dependent upon the eggs as an abundant predictable food supply. The birds stop at just a few places during their spring migration. At each stopover, they have limited time to meet their food requirements before they move on. Weather delays or reduced food supplies at critical stopovers can have significant effects on adult shorebird survival and breeding success.

Threats to Survival

Shorebirds face many potential threats as they travel from the tip of South America to the Arctic. The threats at their stopover areas in South America and Delaware Bay are of most concern because the birds are heavily concentrated in a few areas for very short time periods. Potential threats in these areas include oil spills and other pollution; loss of habitat from development, shoreline alterations, and sea level rise; disturbance from human activities; competition with gulls for food; and reduced food availability.

Since Delaware Bay is the last stopover for shorebirds en route to the Arctic, it is their last chance to gain sufficient energy reserves for the breeding season. It appears that with sufficient food available, the birds can make up for some deficiencies farther south. For this reason we need to help ensure that shorebirds have enough food to meet their needs while in the bay.

A Fishery Management Plan for Birds?

During the 1990s, horseshoe crab harvesting substantially increased. The crabs are used as bait to catch eel and conch for overseas markets. Concern was raised that the level of harvest was reducing the egg supply for shorebirds. In 1998, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, representing 15 states from Maine to Florida, developed a horseshoe crab management plan to address this concern. The ASMFC plan and its subsequent addenda established mandatory state-by-state harvest quotas and created the 1,500-square-mile Carl N. Shuster Jr. Horseshoe Crab Sanctuary off the mouth of Delaware Bay. Recent addenda further reduced harvest in the Delaware Bay area and established a closed season to help ensure that shorebirds have sufficient eggs to feed upon.

Watermen have voluntarily reduced their use of horseshoe crabs as well. Conch and eel fishermen have been using mesh bait bags in their traps, so they use only a small portion of one crab per trap, compared to using a whole crab in each trap. The bait bags have largely reduced the demand for bait by 50 to 75 percent in recent years. Research is also being done to identify alternative baits for the conch and eel fisheries to further reduce the need for horseshoe crabs.

Despite restrictive measures taken in recent years, horseshoe crab populations are not showing immediate increases. Because horseshoe crabs do not breed until they reach nine or more years of age, it may take some time before the population measurably increases.

You Can Help

When humans approach birds too closely on the beach, the birds take flight and move to other areas. This uses energy that could be used to build up their fat reserves for the long journey ahead. When using the beach, keep a safe distance so the birds do not stop feeding and take flight. View them from a distance with binoculars or spotting scopes. Use designated viewing areas and photography blinds when available. If you have a dog with you, keep it on a leash. Keep cats indoors. Limit motor vehicle use on the beach to designated areas.